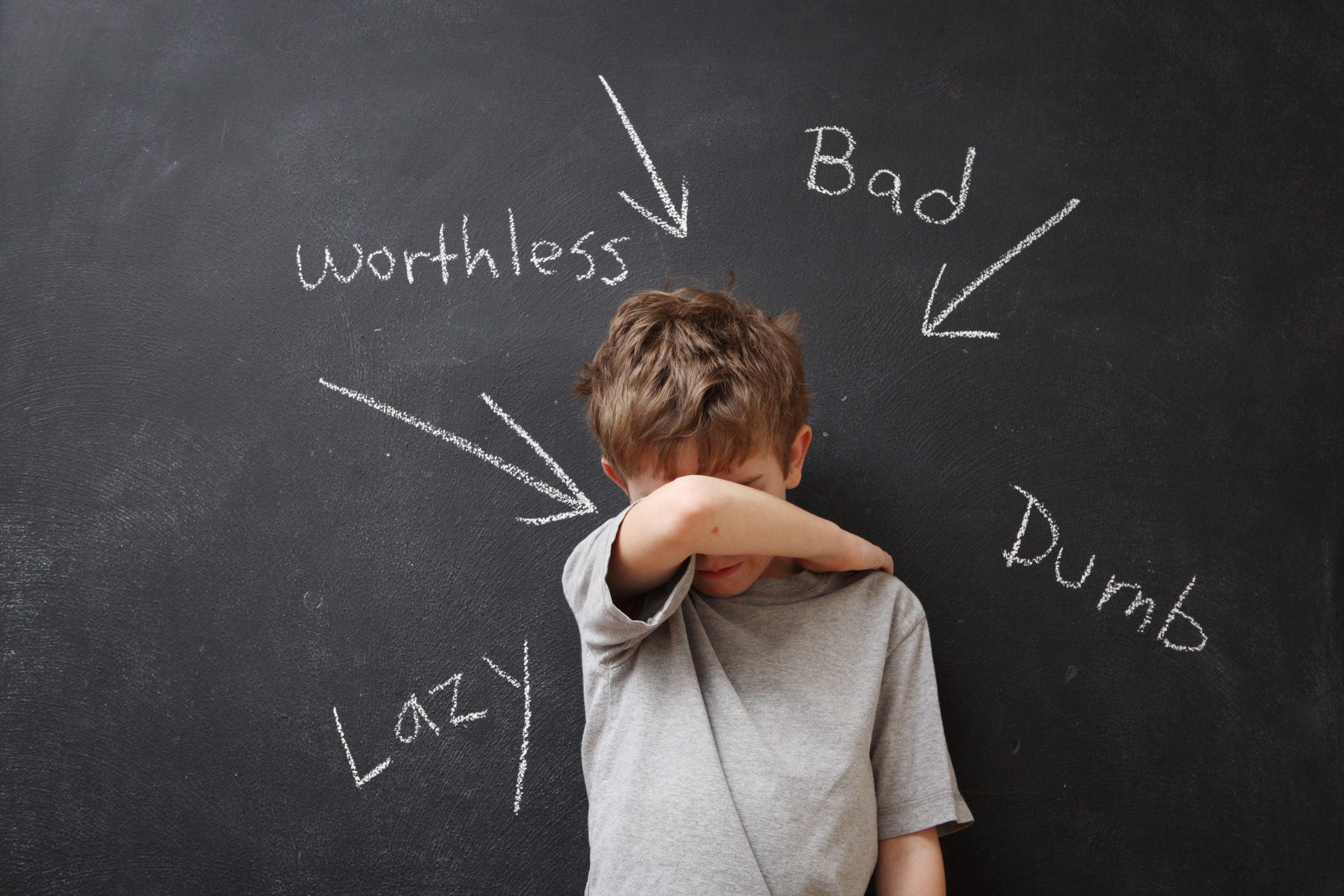

For the most part, education is designed to meet academic demands, which does not always support the development of emotional intelligence of our children. When we as educators and parents put too much emphasis on academic abilities, we may create a culture of shame. Frequent comments about children’s academic performance and measuring their worth in grades often leads to shaming and making them feel that they are not good enough.

So how do we motivate our children to learn without creating a culture of shame and foster a culture of vulnerability while building children’s resilience to shame? First, we must understand the nature of shame. Brene Brown in “Daring Greatly” draws a distinction between shame and guilt. She describes shame as “I am not enough,” and guilt is “I did something wrong”. Shame is focusing on the self, and guilt is focusing on the behavior. Shame damages young people’s sense of worth. Guilt can be productive and help change behavior. And vulnerability can not only help build children’s resilience to shame but also foster confidence through developing creativity.

So how do we motivate our children to learn without creating a culture of shame and foster a culture of vulnerability while building children’s resilience to shame? First, we must understand the nature of shame. Brene Brown in “Daring Greatly” draws a distinction between shame and guilt. She describes shame as “I am not enough,” and guilt is “I did something wrong”. Shame is focusing on the self, and guilt is focusing on the behavior. Shame damages young people’s sense of worth. Guilt can be productive and help change behavior. And vulnerability can not only help build children’s resilience to shame but also foster confidence through developing creativity.

What exactly is a culture of shame and how does it look in afterschool and at home? This question brings me to thinking about my story. Before I was born my whole family emigrated from the Dominican Republic. My mother with her four children spent some time in Puerto Rico where she had me and my twin sister. When I was four years old, we – a family with six siblings – moved to the Bronx. My mom had very high expectations for education, which on the one hand I am grateful for as it led me to the work I’m doing today, but on the other hand, I hold responsible for my lifelong struggles with self-worth and confidence. After reading about the culture of shame in Brene Brown’s book and reflecting on my childhood, I realized that my large family did promote a culture of shame. There was a lot of comparing, especially for me as a twin, coming from my mother and the rest of my siblings. I was constantly compared to the one who was smarter than me and more likely to succeed. As much as it helped to finally understand what a culture of shame was, it did not undo decades of shaming I had lived through.

I remember, for example, being told that I couldn’t read as well as my sister could and that I wouldn’t achieve anything in life because of that. Such comments created confusion between what I believed I could do and who I believed I was, essentially what I thought about myself. Unfortunately, as adults, we often say things without thinking them through unconsciously repeating what we have learned from our parents or during our own educational experience rooted in the culture of shame. As educators and youth professionals, however, we have an opportunity to identify the elements that create a culture of shame and redesign our structures, practices, and behaviors to promote resilience to shame among young people we work with. If we understand where shame originates, we can support our children and show them that they are not their shame. We can also cultivate a culture of vulnerability that will foster creativity, promote confidence, and increase our children’s self-worth.

It might be obvious that my mother turned out to be an authoritative parent figure. When raising six children on your own as an immigrant, it is hard, maybe even impossible to remain conscious of everything you say and know exactly how it influences each child individually. She was a disciplinarian with no tolerance for lack of education even though she herself didn’t finish high school. “Education is possibilities,” she would say. “You can have a life I never had, but for that, you need to study well and work hard.” So, I did. But the problem was that my “studying well and working hard” was not good enough for neither my mother nor my siblings who always reminded me about that. My twin sister, on the other hand, was exceptional and only brought straight A’s home. And for as long as I can remember, I lived in her shadow and was constantly compared to her achievements, always hearing “You can’t. You will never achieve anything. You are not good enough.”

This is a prime example of shame, which unfortunately is still more prevalent in the modern-day education system than you can imagine. Competition is certainty good, but where is the line between healthy motivation and encouragement to try harder, and shaming our children for not being good enough, which Brene Brown describes as “the culture of never enough”? The problem is that the answer to this question is “It depends”. What may encourage and motivate some kids will destroy others, which is exactly what happened to me. To this day even after raising my two incredible sons, building a successful business, and establishing myself in my community, I still feel the shame and the pain those childhood labels brought to me. People can look at you from the outside and think that you “have it all”, but you still feel like that little girl who was never enough.

Years after being shamed in childhood and adolescence for not getting good grades in school, I was at last diagnosed with a learning disability in college, which lifted some weight off my shoulders. I finally heard for the first time “You are not stupid. You just see and hear words differently.” Being diagnosed with a learning disability helped me realize that I was different in my learning process, which did not mean “not enough”. I understood that the problem was not in who I was, but in how I learned.

As adults, most of us develop certain defense mechanisms and establish a more or less strong sense of self. Children and teenagers, on the other hand, are very vulnerable to shame because they don’t yet know who they are. So as educators and caregivers we need to protect them from feeling that they aren’t good enough. We must pay attention to each and every child we work with and provide them with tools to address their limitations, and most importantly discover and develop their strengths. Kids are considering teachers and caregivers their main authority, so the value they put into their words is very high. What we say to our children matters, we must never forget that!

Every child is beautiful and has unique abilities, which, if paid attention to, can grow into real talent. Sr. Ken Robinson, one of my personal role models, emphasizes the importance of courage when facilitating creativity. But we can only be truly courageous in our creativity if we feel safe to be who we are and show it to the world. So perhaps we should spend less time exercising our authority with children, and instead focus on creating a safe, nurturing environment which allows them to be seen, heard, and understood. Creativity inspires confidence. When we have the freedom to do what we are good at, we gradually become more confident to pursue our dreams and live the life we truly want. When children are in creative states, they are radiating joy, growing academically and personally, and develop their talents and personalities. And it is up to us, educators and caregivers, to empower them to do all that and help them be who they are.

Our primary focus should be moving away from a culture of shame and fostering creativity and creating a culture of vulnerability instead. I can outline the following three steps that can help us achieve that:

1 – Being self-aware.

We need to get in touch with ourselves and understand our triggers. We need to be honest and be able to say, “This is my truth, and this child’s behavior is triggering me.” This will allow us to address the situation differently and start healing our own wounds instead of projecting our pain and trauma onto those we care for.

2 – Being socially aware.

We have to learn how to read emotions and interpret the behavior of young people we work with. Are they acting out because of shame or are they simply having a bad day? We need to be able to distinguish between the two.

3 – Establishing efficient communication.

Finally, we have to find ways to establish clear, honest, supporting communication with our children. We need to learn how to communicate if we want to teach our children how to do that. We need to create opportunities for an honest dialogue, allowing them to speak up and tell us how they really feel. Is it always positive? Not at all. Because it means that we always say the truth, which can be uncomfortable.

We must be able to say, “Let’s talk about how we both feel, what we can learn from this situation, and how we can grow together.” We need to be real and allow ourselves to be as vulnerable as possible. I am convicted that anyone would benefit from living this way, but I know that educators and caregivers are those who need it the most.

I would like to share two of my favorite Ted Talks: Listening to shame by Brene Brown, and Changing the Education Paradigm by Sr. Ken Robinson.

For breakfast, I had an egg and cheese wrap with my coffee.

Author: @soniatoledo

Marijane Cochnauer

This article spoke to me and that little girl inside that feels that I am not enough at times. I love brining vulnerability into conversations with school age staff because it helps us trust each other and build true connections with each other and the students we work with. This is why I focus on the phrase You Matter, because we all need to feel that we matter just as we are.

Sonia Toledo

Marijane! Your comment resonates with me deeply. By embracing vulnerability, we can nurture authentic connections among educators and youth. We all deserve to be seen for who we are and feel valued. It is truly inspiring to see your commitment to fostering these connections. Thank you for sharing your insights!