We are honored to share this blog post provided by the National Youth Leadership Council. The original blog post is written by: Dr. Robert Shumer, NYLC Board Member, University of Minnesota, and Tiveeda Stovall, University of San Diego.

America is in its second decade of the 21st century.

While the situation is improving in areas of employment rates, health coverage, and increased graduation rates, there are major changes occurring in the US culture and landscape.

The impact of technology, global economy, and apparent deterioration of civic engagement and political participation (American Civic Forum, 1994; Lipset, 1995; Putnam, 1995; Putnam, 2000) has fundamentally altered life. Worse, there is a renewed increase in both income and social inequality that has altered the opportunities for racial/national minorities to experience social justice and improved quality of life.

With these impending challenges, there is good news. We have opportunities, through well researched educational and social practices, to improve conditions all across the country, especially for youth in schools and colleges. The overriding effort is offered through programs that increase engagement in all aspects of life, from social engagement, to educational engagement, to civic engagement.

Programs that embrace service- learning, volunteerism, and experiential learning provide the activities that allow young people to connect with their communities and their social environments to becomeactive contributors to the improvement of the quality of life for others, and as a result, improve the quality of life for themselves. Service-learning, volunteerism, and community involvement provide the opportunities to reclaim the democratic, humane principles that honor the values and traditions of America.

Research on Service-Learning and Civic Engagement

The modern service-learning movement has been around since the 1960s. Programs have developed in schools and colleges for decades, accelerating in the 1990s and 2000s with the infusion of funding from the Corporation for National and Community Service and several philanthropic foundations. Yet, with the CNCS loss of funding after 2011, the expansion of service and civic efforts in schools and colleges has stalled a bit. Hopefully, legislators and educational professionals will realize the great need to support and expand efforts so we can effectively address the great challenges faced by youth and our country in making democracy and social justice thrive again.

Service-learning has been shown to be a critical element in addressing issues of educational success and improved opportunity for minorities and all students who suffer from lack of engagement in school and society. Two major studies and reports, The Silent Epidemic (Bridgeland, et al 2006) and Engaged for Success (Bridgeland,et al,2008) have shown that service-learning, work-based learning, and apprenticeships are identified by more than 80% of the participants as being the kind of educational programs that would keep students in school.

In addition, they demonstrate that the strength of service- learning and these other related active learning programs is found in its ability to engage youth in pro-social activities that allow them to contribute to the well-being of others and as a result, helps to improve their own personal well-being and sense of value and efficacy. This strength addresses the primary reason students drop out of school:

Nearly half (47 percent) said a major reason for dropping out was that classes were not interesting. These young people reported being bored and disengaged from high school. Almost as many (42 percent) spent time with people who were not interested in school. These were among the top reasons selected by those with high GPAs and by those who said they were motivated to work hard. (Bridgeland, et al, 2006).

Thus, by addressing the issues of boredom and disengagement service- learning can and does produce the kind of connections necessary to both keep students in school and increase their motivation to actually do interesting projects that lead to substantial learning and connection with community.

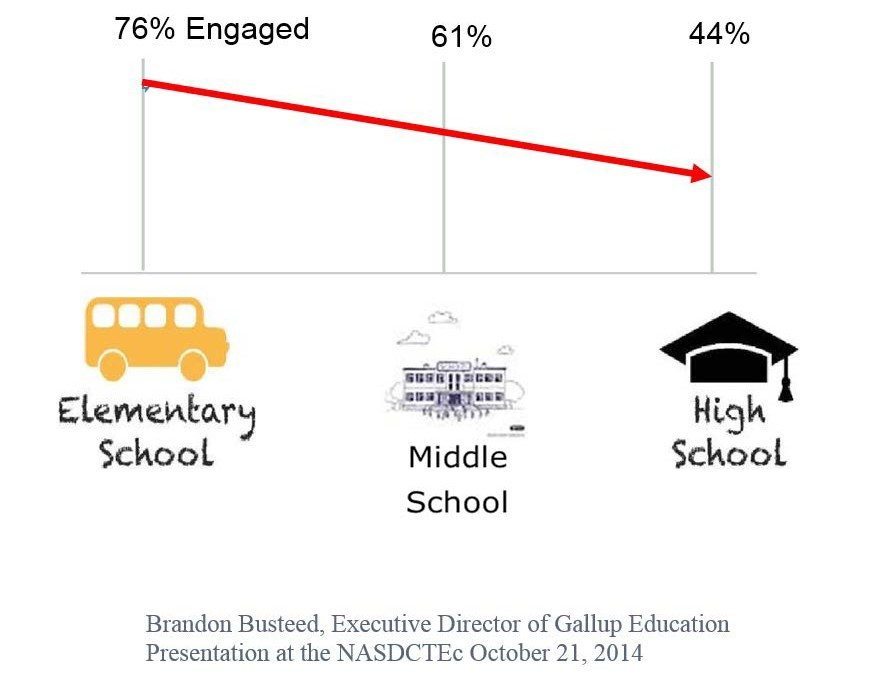

Engagement issues increase the longer students remain in school.

In fact, by the time students reach high school, more than half report being disengaged from school.

A parallel stream of research and practice focuses not just on the impact of civic engagement on the recipients of services, but rather the benefits for those who engage. The theory and practice of Positive Youth Development (PYD) provides considerable evidence that young people develop in healthier ways when they are given opportunities—or even mandates—to be civically engaged (Eccles and Gootman 2002; Lerner 2004). Longitudinal studies show that young people who serve their communities and join civic associations succeed in school and life better than their peers who do not engage. (Dávila and Mora 2007). Those findings are supported by experiments using PYD programs (e.g., Hahn, Leavitt, and Aaron 1994).

Issues of boredom and disengagement begin to increase the longer students remain in school. More than half of high school students report being disengaged from school.

In studies of adolescents and young adults, volunteerism and collective action are directly connected to various areas of social well-being. These include self- efficacy, hope, and optimism (Uslaner, 2002).Other work has shown impact on collective efficacy and self-confidence (Astin and Sax, 1998). and self-esteem (Thoits and Hewitt, 2001). Specific studies of service-learning in high school and college have found relationships with students’ feelings of agency, efficacy, purpose and meaning in life, interpersonal skills, and living up to one’s potential (Astin, et al. 2000; Markus, Howard, and King, 1993; and Youniss and Yates, 1999).

Studies show that young people who serve their communities and join civic associations succeed in school and life better than their peers who do not engage.

The above mentioned concern for dropout prevention does not just affect school completion.

It influences all aspects of civic involvement, from voting, to participating in all areas of community life. The Silent Epidemic report suggests: The most dramatic divides in civic health related to levels of education. College graduates outperform their less educated peers in every civic category, from volunteering and work on community projects, to attending meetings and voting. For the most part, high school dropouts are no longer even a part of the civil society that would enable them to be effective advocates in their communities and states for efforts to reform high schools. They suffer both from a lack of learning and a lack of service.

Thus, anyone concerned with the preservation of democracy and healthy communities must attend to issues of educational success. The fact that only about 20% of the 18-29 year olds in the US voted in the 2014 election should be great cause for concern about the health of our democracy (CIRCLE, 2015). This was the lowest turnout for this age group ever recorded. Clearly developing programs such as service-learning and other efforts to actively engage students in their communities is of critical importance.

Research confirms that doing classroom- based civic education makes a difference in producing knowledgeable and connected students.

A major study of the Chicago schools (Kahne and Sporte, 2007) reported that classroom-based civic learning opportunities mattered.

Kahne and Sporte find that students’ racial and ethnic backgrounds have very little impact on their civic commitments, once other factors are taken into account. The civic engagement of their families and neighborhoods do matter, but the impact of service-learning and other classroom- based civic learning opportunities is substantially larger. Being required by teachers to keep up with politics and government and learning how to improve the community, for example, are highly effective forms of civic education. There are also statistically significant effects from other teaching methods, such as exposing students to civic role models. Kahne and Sporte find positive effects from participating in afterschool programs, but the effect sizes are smaller than those attributed to civically oriented classroom activities such as service-learning and classroom discussions of current issues.

So, service-learning is not only important for helping students to graduate and get connected to community, it is a documented approach to improving civic learning and participation in democratic society.

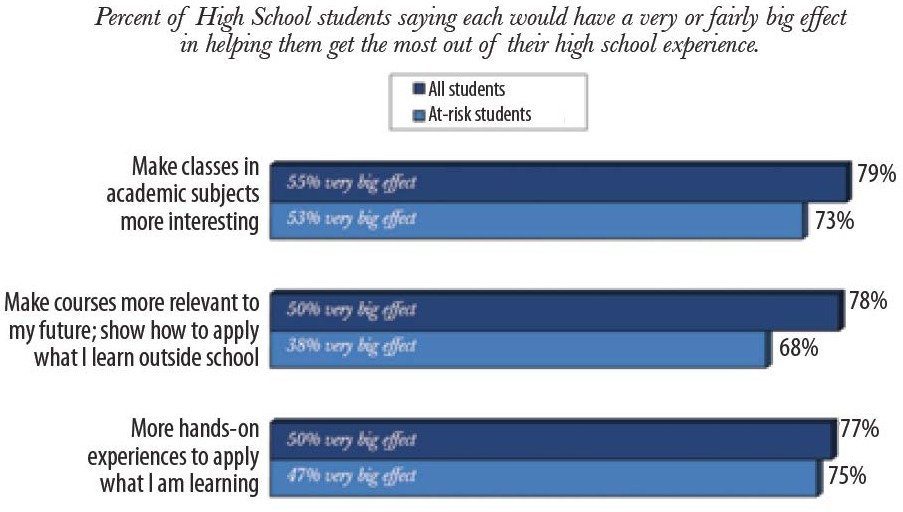

This notion of engagement and interest is not just limited to potential dropouts. It, according to the Engaged for Success report, actually affects all students. Results from both regular students and those at-risk of dropping out report that making academic learning more interesting, making it more relevant to their lives, and providing more hands-on learning is what is needed to improve the quality of education in all schools.

Thus, programs that make classes more interesting, more relevant, and more experiential in format are the ones that will make schooling more engaging and more educational. Service-learning clearly contains all these elements and is/ should be a model effort to address all the challenges of the educational system. Implementation of service-learning in schools will go a long way to addressing issues of deterioration of community, decline of civic engagement, improved academic performance, and improved involvement of young people in the principles and actions of democracy. Service-learning should be considered by every policy group that is concerned with the conditions of education and society today.

Making learning more interesting and relevant to everyday life is important for quality education and keeping high school students in school.

Engagement, School Climate, and Academic Achievement

Engaged students have to show up to school to be engaged. You cannot do well in school if you do not show up (Fisher, Frey, and Lapp, 2011).

It’s a simple enough premise but disengaged and sometimes, disenfranchised students of color and other marginalized students are not present at the table of academic aspirations. Fisher et.al. (2011) explored closing the achievement gap by looking at student attendance and engagement. The high school population in their study was comprised of 72% students of color, 60% Title I eligible, and 70% spoke English as a second language.

Fisher et al. (2011) reviewed student attendance at the onset of the study and found that the lowest-performing students missed an average of 6.5 days of school per month while the highest performing students missed an average of 1.8 days per month. Researchers employed an intervention where students were allowed an increased amount of international, open exchange discussions among students in the classroom. At the same time, the amount of teacher “talk” to students decreased in the classroom thereby highlighting more student voice. The study results showed the interventions increased attendance by 5.3% and had significant improvements on standardized tests scores post interventions by as much as a 19% improvement (Fisher, et al., 2011).

Drawing from Purkey and Novak’s 1996 theoretical framework of invitational education, where everyone in the school climate is invited to experience success, Vega and Miranda (2015) examined African American and Latino high school students’ perceptions of educational barriers to positive experiences in school. The study represented six high-poverty schools in Florida where students, teachers, counselors, and peers completed questionnaires and interviews based on the invitational education’s five “P”s: people, policies, programs, processes, and places. These five “P”s serve to inform school settings on the messages transferred to students which impact their perceptions of learning. Vega et al. (2015) discussed “places” results from the study which noted how participant students felt safe at school, the feeling of safety did not carry over to the neighborhood in which they lived. The researchers noted a study in which community violence associated with decreased math and reading scores. Herein lies an opportunity. An opportunity to engage students, districts, teachers, parents, and community in social justice, social change, and academic advancement.

Critical Service-Learning and Social Justice

“Many activities in life, including education, become difficult undertakings for students constrained by severe social injustices. When these social injustices are engaged and critiqued, students begin to clear intellectual and emotional space for education. They become further engaged in learning when their education becomes a means by which they may challenge oppressive forces within their social contexts.” (Cammarota, 2007)

In 2007, Tania Mitchell linked the concept of service-learning and social justice education to illuminate the pedagogy of critical service-learning to engage students in transformative service with communities. Critical service- learning focuses on social justice outcomes by having students analyze the root causes of injustice and the imbalance of power structures while promoting student agency in the ability to create social change (Mitchell, 2008). The tenets of social justice education and critical service-learning can serve as a motivator to engage marginalized students toward academic engagement and success. Social justice education launches from students’ lived experiences and acknowledges student viewpoints on the most pressing problems they face and which face their communities (Wade, 2001).

Julio Cammarota (2007), piloted and researched a social science curriculum, the Social Justice Education Project (SJEP), targeting Latina/o students and their perspectives on their potential to graduate high school and advance to college. SJEP engaged students in participatory action research to think critically about the social issues which impeded their progress. Within the first cohort of students, many students were labeled “at-risk” of dropping out. The students developed and participated in action research around four topics: (1) cultural assimilation, (2) critical thinking vs. passivity in education, (3) racial and gender stereotypes of students, and (4) media representations of students of color (Cammarota, 20007). Students investigated topics with peers, school members, and community. Students then presented recommendations to both school officials and community members on areas focused on 1) better media relations with students of color, 2) improving multicultural education, 3) expanding critical thinking in education, and 4) ways to prevent racism and stereotyping (Cammarota, 2007). Although Cammarota noted that many of the recommendations were not taken up by officials, the positive impact of the social justice curriculum and critical service-learning led 15 of the 17 student participants to graduate while the other two prepared for taking the GED.

The Stanford CEPA Working Paper

“When students’ lives and experiences connect with the curriculum, they become more invested in their education (Trueba, 1991).”

With the makings of becoming a seminal work of research, Stanford’s Center for Education Policy Analysis published “The Casual Effects of Cultural Relevance: Evidence from Ethnic Studies Curriculum” (Dee and Penner, 2016). The paper reports data over a five-year span on 1,405 students during their 9th-grade year in the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD). Participating students were identified as “at-risk” of dropping out of school, with GPAs below 2.0. Students assigned to take an Ethnic Studies course incorporated culturally relevant pedagogy, as social justice education, and critical service-learning pedagogy as tools to support marginalized students of color.

“The course also encouraged students ‘to explore their individual identity, their family history, and their community history’ and required students to design and implement service-learning projects based on their study of their local community. The designers of this curriculum hoped that these lessons and projects would increase students’ commitment to social justice and improve self-esteem.” – (Dee et al., 2016, p.10)

The ethnic studies project piloted in the 2010-2011 academic year with five high schools in SFUSD with the explicit statement that the Ethnic Studies course and components would contribute to closing achievement gaps. The SFUSD school board voted to expand the Ethnic Studies course to all 19 high schools by the end of 2014. Findings from the study revealed positive gains. Student GPAs increased an average of 1.4 points. Students earned an increase of 23 credits and attendance at school improved by 21 percentage points (Dee et al, 2016).

Social Justice Curriculum

“This is not a moment, It’s a movement” – Black Lives Matter

An important note was made in the Stanford CEPA paper on the significance of its findings. The degree to which this study might be replicated is dependent on applying the amount of preparation, planning, duration of the course, and integrity that went into this program intervention. The study did illuminate “proof of concept” that academic gains can be made by engaging students in curriculum and activities which reflect their lives (Dee et al, 2016).

Though scalability seen at SFUSD may not be available to most schools or districts, there are accessible resources to begin the development of social justice education and critical service- learning through online resources. In January 2012, the FAIR (Fair, Accurate, Inclusive, and Respectful) Education Act went into effect in the state of California. Free standards-based curriculum to support educators in the law is available on the FAIR Education Act website at https://www. faireducationact.com/. The Fair Education Act amends the California Education Code to require courses of study and instructional materials:

“51204.5. Instruction in social sciences shall include the early history of California and a study of the role and contributions of both men and women, Native Americans, African Americans, Mexican Americans, Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders, European Americans, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender Americans, persons with disabilities, and members of other ethnic and cultural groups, to the economic, political, and social development of California and the United States of America, with particular emphasis on portraying the role of these groups in contemporary society.”

Social justice curriculum has been developed on specific topics ranging from combating human trafficking from the Fredrick Douglass Family Foundation to environmental justice in Flint, Michigan from Discovering Place. When five school librarians came together to compile online

#BlackLivesMatter curriculum for the San Francisco Public Libraries and local school district, they validate youth voices, to engage and connect in classrooms, on what they were experiencing in their neighborhoods and national communities. These tools for engagement, with thoughtful and authentic application, could ignite increased academic achievement for marginalized students.

References

- Astin, A. W., and L. J. Sax. 1998. “How Undergraduates Are Affected by Service Participation.” Journal of College Student Development 39 (3): 251–63.

- Astin, A. W., L. J. Vogelgesang, E. K. Ikeda, and J. A. Yee. 2000. How Service Learning Affects Students. Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute.

- Bridgeland, J., Dilulio, J., and Morison, K. (2006). The silent epidemic: perspectives of high school dropouts. Civic Enterprises, in association with Peter D. Hart Research Associates for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

- Bridgeland, J., Dilulio, J., Wulsin, S. (2008). Engaged for success: service-learning as a tool for high school dropout prevention.Civic Enterprises, in association with Peter D. Hart Research Associates for the National Conference on Citizenship.

- Cammarota, J. (2007). A social justice approach to achievement: Guiding latina/o students toward educational attainment with a challenging, socially relevant curriculum. Equity & Excellence in Education, 40:1, 87-96, DOI: 10.1080/10665680601015153

- Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE). Quick Facts from civicyouth.org/quickfacts/youth voting. Tufts University. 2016.

- Dávila, A., and M. T. Mora. 2007. “Civic Engagement and High School Academic Progress: An Analysis Using NELS Data.” CIRCLE working paper 52, Jonathan M. Tisch College of Citizenship and Public Service, Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, Tufts University, Medford, MA. https://www.civicyouth.org/PopUps/ WorkingPapers/WP52Mora.pdf.

- Dee, T., & Penner, E. (2016). The casual effects of cultural relevance: Evidence from an ethnic studies curriculum (CEPA Working Paper No.16-01). Retrieved from Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis: https://cepa.stanford. edu/wp16-01

- Eccles, J., and J. A. Gootman, eds. 2002. Community Programs to Promote Youth Development. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Fisher, D., Frey, N., & Lapp, D. (2011). Focusing on the participation and engagement gap: A case study on closing the achievement gap. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 16(1), 56-64.

- Hahn, A., T. Leavitt, and P. Aaron. 1994. Evaluation of the Quantum Opportunities Program (QOP): Did the Program Work? Waltham, MA: Brandeis University.

- Kahne, J. and Sporte, S. (2008). Developing citizens: the impact of civic learning opportunities on students’ commitment to civic participation. Civic Engagement Research Group. American Educational Research Journal, September 2008, Vol. 45, No. 3, pp. 738-766.

- Lerner, R. M. 2004. Liberty: Thriving and Civic Engagement among America’s Youth. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Markus, G. B., J. P. F. Howard, and D. C. King. 1993. “Integrating Community Service and Classroom Instruction Enhances Learning: Results from an Experiment.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 15 (4): 410–19.

- Metz, E. and Youniss, J. (2003). “A demonstration that school-based required service does not deter, but heightens, volunteerism. PS: Political Science & Politics 36 (2): 281-6.

- Thoits, P. A. and L. N. Hewitt. 2001. “Volunteer Work and Well-Being.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 42 (June): 115–31.

- Trueba, H. T. (1991). From failure to success: The roles of culture and cultural conflict in the academic achievement of Chicano students. In R. R. Valencia (Ed.), Chicano school failure and success: Research and policy agendas for the 1990s (pp. 151-163). New York: Falmer

- Uslaner, E. M. 2002. The Moral Foundation of Trust. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Vega, D., Moore III, J.L., & Miranda A. H. (2015). In their own words: Perceived barriers to achievement by african american and latino high school students. American Secondary Education, 43(3), 36.

- Wade, R. (2007). Service-learning for social justice in the elementary classroom: can we get there from here?, Equity & Excellence in Education, 40:2, 156-165, DOI: 10.1080/10665680701221313

- Youniss, J., and M. Yates. 1999. “Youth Service and Moral-Civic Identity: A Case for Everyday Morality.” Educational Psychology Review 11 (4): 363–78.