When we were the age of our students, neither of us thought that we would be teachers.

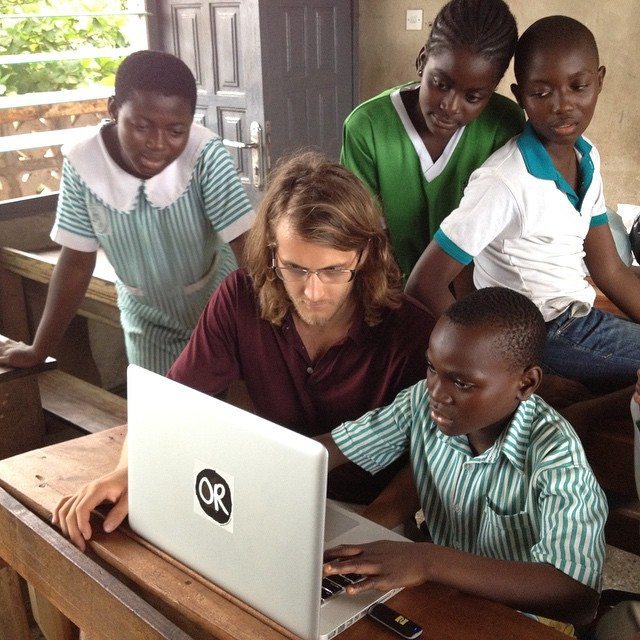

Even in 2011, when we first entered a classroom to foster relationships between learners across borders, we didn’t consider the possibility that we would end up working in education. But today neither of us could imagine doing anything else. While our path toward becoming educators has not been a traditional one, our mission as co-founders of the not-for-profit organization The OR Network has grown organically. When the two of us first met we were both working in the fashion industry in New York City. Liz, a trained fashion designer, worked as a stylist and design consultant. Branson, just then finishing up his course of Globalization of Public Health and Societies through NYU’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study, managed a fair trade fashion cooperative. We started working together because both of us wanted to transform the fashion industry into something as beautiful as the clothes it sells. What we’ve realized since then is that to fill the fashion industry, or any industry, with compassion, connection and fairness we first need to change education.

Today there are at least 35 million people enslaved.

As a global community, we are also facing an environmental catastrophe. Needless to say, these challenges are enormous and deeply engrained in the fabric of the predominant culture that has spread through the various mechanisms of globalization, including the fashion industry and education. So to tackle these challenges, education needs to be the core of any strategy. We don’t mean education in the sense of getting every child into school like the Millennium Development Goals suggest. That’s a great effort and necessary, but not our focus. We mean education in the sense of what children learn once they are in the schools. Education can play a huge role in shaping a culture that stands up against modern day slavery and works to preserve the environment by treating other people and the planet with compassion and kindness. This is not just an ideal, but a truth we have seen in action.

Over the past four years we have developed a program to help students define healthy values – aspirations and desires – for themselves. We call this program Collectofus Global Leaders. Through this program, students in Accra, Ghana, Vaalwater, South Africa, Detroit, Michigan, Brooklyn, New York, Cincinnati, Ohio and Washington, DC have exchanged scarves and videos that they created for one another. Students then interact through the online platform Collectofus.org that we have built for the program, and they learn together through a curriculum that we have designed based on the history of their t-shirts, clothing that students in every location wear regularly. Running this program with over 500 mostly middle school age students has taught us few things that we think might be useful for anyone seeking to nurture empathy and leadership for change in our fellow citizens.

6 Tips for Nurturing Empathy and Leadership

1. Service learning is a two way street.

Learning does not happen if students think they are helping other students, because it immediately skews the power dynamic. This is not something we want to teach. We want our students, regardless of their backgrounds, to work together and see similarities as much, if not more, than they see differences. Students in our programs do not travel to other places. As a microcosm of global trade, the objects that students make travel, but the students stay in place. The fact that one group of people can, with relative ease, go to a place that another group of people can’t leave is not necessarily a good thing.

2. When developing partnerships for learning, plan for different expectations of time, communication breakdowns, technical difficulties and the unforeseeable.

Notice that the unforeseeable gets its own category of planning because the first three things to plan for are all foreseeable. This requires as much flexibility from teachers and facilitators as it does from students. Instead of trying to solve issues out of our control as educators, use the issues as learning opportunities. For instance, the fact that students in one school haven’t been able to get on the internet for months can become a lesson in perspective. The way teachers approach this concept can serve as a valuable model for students.

3. Asynchronous communication is key.

While the novelty of Skype and other video chatting services is great, connection issues, language barriers and time zone differences mean that meaningful conversations simply will not happen through real time communication. Students need time to reflect, research and prepare responses and questions for their peers. This is just as applicable for communication between teachers.

4. Emotional learning takes time.

Having one or two interactions may make for a few moments of excitement, but numerous and consistent interactions over the course of the year can transform the way students think. Consistency allows for students to work together and to develop the real relationships that will challenge stereotypes and develop empathetic values for a lifetime. Consistency is not easy to achieve and must be a priority.

5. Students need to reach their own conclusions.

We want students to believe in and act on the values that they say they hold dear. To do this those values must be based on students’ own experiences. As teachers, we can beautifully and passionately convey a message. Yet for students this second hand knowledge is not as powerful as what they know to be true from their own experience. It is our responsibility as teachers to facilitate a forum in which students can process and extract meaning from their experiences.

6. Experience inspires love.

This last point is something that our students have directly communicated to us. In the most recent Collectofus Global Leaders exchange, a student in South Africa innocently told his peer in Washington, DC that he loves him. (In fact, the student in South Africa had looked up how to say ‘I love you’ in Spanish, his DC peer’s native language – “te quiero.”) This sparked a fascinating conversation back in the classroom in DC. Students agreed that saying ‘I love you’ is something that they don’t do often enough. They only say it to peers after an “experience.” The students said that summer camp is an experience that would leave them telling their peers ‘I love you.’ While the students said that their exchange with their peers in South Africa was such an experience as well, none of the students considered school as an “experience.” This really made us think. Why is school not an experience that inspires ‘I love you?’ How can we expect students to shape their worlds with compassion if they are not moved to love by what they are learning?

This question of experience brought us back to where and why we started our organization four years ago. When we ran what we thought then was to be a small side project connecting students between an after school program in Brooklyn, New York with students in Accra, Ghana, we were surprised and struck that none of the students in Brooklyn had anything to ask their peers in Accra. How could it be that young people, who are so naturally curious, couldn’t come up with questions to ask of their peers in a far away place?

This inability of the students to connect was no fault of their own. It was a result of an education that had dehumanized the globe, making far away places a series of numbers and statistics where ‘those people’ live in ‘that place.’ We observed that students in Brooklyn were afraid of asking the wrong question. They didn’t know how to interpret the statistics of African tragedy that they knew into something personal that wouldn’t offend their peers or sound trivial. This was so far from the compassion and connection that we hoped to see. Meanwhile in Accra, students had no problem sharing and asking questions. It made us realize that something big was missing from our student’s education in the United States and it inspired us to grow our small side project into our full time focus. This phenomenon — the one-sided inability to connect — has continued as we’ve worked with more students on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. We’re relieved to say that by the end of our year-long program almost all of our students interact freely, ask inspired questions and listen carefully to the answers.

The thread that runs through these lessons and the foundation of the work that we do is the belief that globalization can and should be a heterogeneous force for good. And that we should hurry up to slow things down. Trying to find a prescriptive solution to an issue is at odds with the diversity that we ask our students to celebrate. The power of a global perspective is that it allows us as lifelong learners to see our own struggles and triumphs in new ways that will help us better them and build on our strengths. Instead of studying other people’s problems, global education can and should focus on our local communities. In doing so, we will recognize the impact of our individual choices and actions on the globe. It takes time to unlearn stereotypes, to practice humility and to rethink value. These changes cannot happen through one homework assignment. They must be reinforced through a curriculum following students’ long-term growth. To do this requires commitment from both individual educators and the institutions in which we work. That very commitment is a model of what we are hoping to instill in our students. We want our students to measure success in their lives not by quarterly grades in education or quarterly earnings in the commercial sphere, but by their long term impact to make the world a better place.

Follow The OR Network on Instagram and Twitter.

For breakfast, we had banana pancakes, made with eggs, flax, coconut flour and obviously bananas. We also had Mesa Sunrise cereal from Nature’s Path. Both had cold brew coffee with organic skim milk and Branson, had a mango smoothie protein shake.

The OR Network began in May of 2011 when Branson, Liz and a cohort of friends connected students ages 4-12 at the Textile Arts Center in Brooklyn, New York with students of the same age in the town of La, on the outskirts of Accra, Ghana. This marked the beginning of an exploration that has since grown into a comprehensive curriculum and much more.

Read more about Branson, Liz and their story on The OR Network website.