Both the evidence from the science of learning and common sense tell us that learning and development occur all the time. But typically, opportunities for learning and development are shared and spread over various spaces, places, and delivery modes in schools, community organizations, and families. But ten days ago, most of those places were abruptly shut down – schools were closed, OST programs shuttered, and parks were ordered emptied. Yet learning and development didn’t stop.

Millions of families, out of a sense of collective responsibility and blunt necessity are keeping their children home, doing their best to bring the full range of social, emotional, learning, and health supports under their own individual roofs. We are watching a national compulsory demonstration unfold. The learning curve for everyone – young people, families, teachers, and OST and community leaders – is steep.

My own family is a microcosm of this demonstration, forced upon us by an unseen, but very real, public health threat. As parents, an educator and former frontline youth worker, both extensively trained in youth development and engagement methods, we should be able to create a reasonably robust living-learning environment for our own kids during this time of crisis, right? We have preparation, support, and resources. Between the two of us, we’ve taught in classrooms, run summer camps, staffed OST programs, and trained youth workers. But the learning curve, without the familiar community and collegial supports, has still been significant. We’re exhausted.

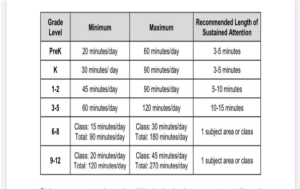

Illinois State Board of Education Remote Learning Recommendations

In our household, we’re taking our “easy wins.” E-learning onboarded with minor snags. We’ve adopted a structure of “rhythms and routines, not strict schedules,” and feel comfortable following our state’s educational guidance for structuring a reasonable learning plan under “the new normal.” We have ideas and energy to facilitate what else might fill developmental space – activities that are typically the provenance of out-of-school time.

The relative grace with which we’ve transitioned is bolstered not just by previous experience in facilitating positive youth development spaces, but also by jobs portable enough to bring home and schedules flexible enough to work around at-home learners. We have mental and physical space for almost nightly “balloon four-square” tournaments, weekend science experiments, a 50-day board game challenge, 3-D printing projects gleaned from online maker spaces, and “quarantine quests” (self- development mini-projects) posted as ideas on our kitchen wall. We’ve been able to bring aspects of their afterschool activities online. We end each day with “highs,” “lows,” and “learnings.” Making lemonade out of lemons is easier when you have some tools with which to squeeze the juice and containers to serve it up.

In contrast, a cousin who lives 20 minutes away, got a printed packet for two kids, a pick-up time to receive Chromebooks from the local school, and the promise of more e-learning supports on the way. But as one of the 1000s of Chicago Public School families with no previous regular online access (though Mayor Lightfoot did negotiate 60 days of free access for low income families), they had to be quickly identified and brought up to speed on an e-learning model that will likely extend for months – one that will likely be rolled out inequitably. Curated content via Google Classrooms and Zoom for some students, and “minimal assignments” (as one CPS parent friend noted via text) for others.

The friend I’ve been texting with sums the situation up: “Even my own kids in the same house are having different COVID 19 e-learning experiences, let alone kids across the district or country.” Using the ‘sigh’ emoji, we agree on two things:

- The level of advanced preparation and support that adults had to quickly adjust learning supports to the new context varied wildly. Many didn’t have clear direction or support on what was expected or even possible to do.

- As individual parents, we’ll figure out how to fill in around “minimal,” but we see clearly that the landscape is not even.

What about the millions of other families who find themselves at a very different point along the continuum of preparation, support and resources, and needing to bring everything home to support a generation for which everything’s been cancelled?

My cousin’s oldest son, the age peer to my own 14-year-old, has to spend portions of the day focused not primarily on his own learning, but watching younger siblings to ensure adults can go to work. There isn’t really a backyard for their two-bedroom apartment, and even without a pandemic, going to the park was an infrequent occurrence, enforced by my cousin under a different definition of safety.

My cousin’s oldest son, the age peer to my own 14-year-old, has to spend portions of the day focused not primarily on his own learning, but watching younger siblings to ensure adults can go to work. There isn’t really a backyard for their two-bedroom apartment, and even without a pandemic, going to the park was an infrequent occurrence, enforced by my cousin under a different definition of safety.

Even as my cousin expresses general satisfaction: “the teachers give them assignments to turn in through the internet” and CPS “has been feeding kids pretty well” – large bags are sent home for each kid (and, agreed, the speed at which districts turned around food distribution plans has been commendable) – the landscape of what happens when out-of-school time is all the time stretches farther than the physical distance of the 10 miles between us.

Taking on additional household responsibilities in the care of siblings, learning how to entertain and keep younger siblings safe for stretches of time with less than 800 square feet is out-of-school time learning as well. But it is learning that lies a bit more under the radar, harder to support and credit despite everyone’s best efforts.

When we have moved past this crisis, what will we have learned about learning, particularly learning which typically occurs in out-of-school time? What will get counted as learning? Which learning might be easier to document in an essay for a summer program or college application? Will the skillsets and mindsets that my cousin is learning under quarantine – those required of “essential workers” for which the entire country is finally gaining a new-found appreciation – be recognized and credited? Hopefully.

More likely, the opportunity (and recognition) gap will remain wide and stand agape even more widely as we try to piece back together OST programs which post-COVID fates are so uncertain. But it doesn’t have to be. We have a grand opportunity to use this time to rethink what’s possible to do, what could be counted as learning (particularly with more targeted support), what can be adapted to evolving circumstances, and reaffirm what matters. We will need our most creative and expansive thoughts, and our fullest, most present hearts when we finally reemerge.

Conversations are already underway about how classrooms will need to be different to address the social emotional needs that this crisis will surface, asking us to learn from this time of development in the age of coronavirus. Let’s be ready to inform and partner in those discussions, having checked in with as many kids as possible to understand their developmental experiences and learn from what they say about their own development in these times. Let us be ready to turn the cancellations of the current moment into commitments that rise to the occasion that the post-COVID developmental landscape will present.

For breakfast, I had a bowl of cereal and a glass of water.

Author: @aliciaw

Alicia is an independent OST policy consultant with affiliations with the Forum for Youth Investment and the Children’s Funding Project. Today, she had a bowl of cereal and a glass of water for breakfast, also with a too steady “diet” of daily news. She’s working to stay balanced and connected in this age of coronavirus.