In the face of strong headwinds…

In Saudi Arabia, women can’t drive. In Lebanon, sexual harassment is legal. And even in the United Arab Emirates – relatively advanced on gender issues among predominantly Muslim countries – men can physically discipline their wives. Across all 22 states in the Arab world, women face legal and cultural obstacles unfamiliar to women in the United States.

Arab Women Push Ahead

One area, though, in which Arab women in fact face lesser obstacles and achieve at a higher rate than their U.S. counterparts is engineering. At a time when the rate of American women graduating from engineering programs has been stalled out at 20 percent for more than 10 years, Arab women have been flocking to the field.

What can burgeoning numbers of Arab women in engineering teach us about problems in the U.S. getting and keeping women in engineering programs? How does this phenomenon shed light on the reasons U.S. women make study and career choices that lead them away from engineering?

The Numbers

For reasons as diverse as the countries themselves, Arab women exceed their U.S. counterparts in enrolling and completing engineering degrees, and it’s not even really close.

Among rich countries:

- Kuwait graduates women at 49 percent of engineering classes.

- Thirty-two percent of engineering students in Bahrain are women.

- United Arab Emirates enrollments increased from 2.9 percent in 2012 to 24.9 percent in 2015.

- Even in Saudi Arabia, graduation rates for women in engineering have risen from one percent in 2000 to 10 percent by 2011. And 80 percent of female students show interest in engineering.

Developing countries do well, too:

- Women are 40 percent of engineering classes in Jordan.

- Algeria’s engineering class is 36 percent female.

- Women in Gaza study computer science and engineering at the same or higher rates than men do.

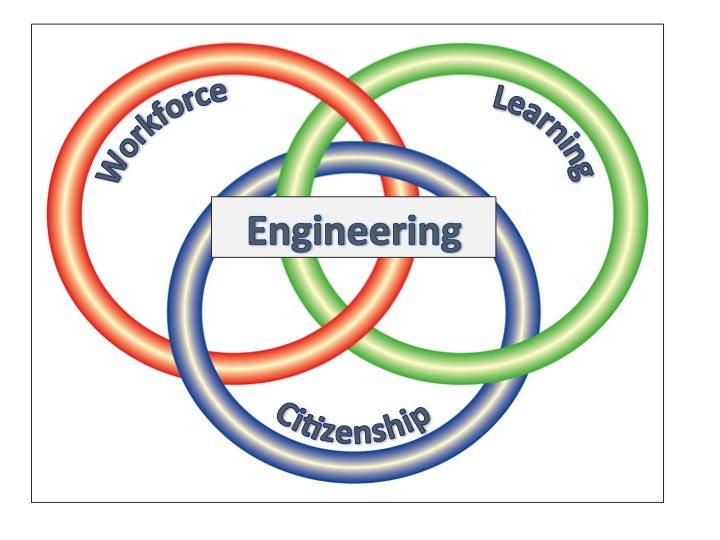

Pathways

For Arab women, the pathways into engineering are, in some ways, more defined and clearer than for American women.

Over three-quarters of Arab governments have taken steps towards developing knowledge-based economies, emphasizing STEM learning at elementary, secondary, and post-secondary levels.

Same-sex schooling, common in Arab countries, means girls study STEM topics in environments that often promote their achievement and satisfaction in these areas.

Test results often drive admissions to college, especially in public institutions. When girls test well in STEM areas, they move more reliably into post-secondary STEM studies than in the U.S., where more diverse areas of study are open to girls.

Engineering’s Appeal

For those girls with engineering aptitude, both cultural attitudes and the prospect of material rewards make the field more attractive to them than it is in the U.S.

Notes Tod Laursen, president of Khalifa University in Abu Dhabi and former Duke University faculty member, “The engineering profession in general holds a lot of prestige in the UAE and we find that the families of our female students are very highly supportive and proud of their daughters, wives, siblings studying these subjects.”

And especially in poorer Arab countries, engineering offers more career stability and better earning power than other paths open to women, such as teaching or public administration jobs. As consumer economies develop more fully at all levels of the Arab socio economic landscape, these calculations come to outweigh traditional views of women that would otherwise keep them at home.

How Engineering Works for Arab Women

In the workplace, Arab women can find meaningful opportunities in engineering and technology fields.

- Startup culture, and the technology industry in general, can be, surprisingly, less gendered in the Middle East. A recent meeting of Internet entrepreneurs in Amman, Jordan, was over one-third women, a rate that attendees confirmed as typical in the field.

- In the United Arab Emirates, government policies promoting nuclear power and robotics have explicitly included appeals to attract women into engineering studies. Women have responded, now making up about half of enrolled students in these fields.

- When Nermin Fawzi Sa’d, a mechanical engineer in Jordan, was looking for help with some projects, she posted a seven-word ad online: “Female engineers required to work from home.” Within a week, she received over 700 resumes. This response led her to form Handasiyat, a virtual engineering consultancy employing female Arab engineers that has grown quickly into a high-profile business.

Making the Best of It

Of course, exactly Sa’d’s requirement to work from home points up one of the reasons that engineering and technology fields can work for Arab women. Women are still expected to run households and take care of children, parents, and husbands. As one Arab woman entrepreneur noted, “Well-educated women in Saudi Arabia want to work, but their family often objects … running an Internet start-up from home is the perfect compromise.”

Indeed, comparable professional paths can be shut off to women. Law and medicine, for example, remain overwhelmingly male because of gender-based prohibitions that preclude women from arguing cases against men in court or treating male patients.

The success of Arab women in engineering shows a few things:

- Girls have all the natural ability they need to succeed in STEM fields.

- Inclusive, supportive STEM pathways can help increase the numbers of girls entering engineering and technology fields.

- Pay and career opportunity matter to women’s professional decisions and identities.

Why Engineering Works More for Women in the Middle East than in the U.S.

It really seems to come down to the values and rewards attached to engineering. Terms like “geeky,” “nerdy,” “uncool,” and, crucially, “for boys only” do not attach themselves to the profession, as they do in the U.S.

Instead, engineering is seen as open, materially rewarding, and socially useful. As a result, Arab women are not departing from gender norms or broader cultural values when they study STEM fields in secondary school, opt into engineering and technology studies, and go to work in a technical field.

Rather, they accrue material and social capital for succeeding in a challenging field that is understood to reflect credit on their abilities, meet a family’s economic needs, and serve a country’s broader, shared interests. And, crucially, engineering offers them opportunities that other, comparable professions do not.

The Takeaway

The culture and meaning of engineering in the U.S. must change.

Bias in engineering is shown to motivate U.S. women to choose other fields or leave early. The field needs to become more inclusive from the inside and appealing from the outside before the rate of women’s participation in the U.S. can break out of its currently stagnant levels.

The example of Arab women’s enthusiastic response to an engineering field constructed to be inclusive, rewarding, and meaningful – even in the face of all the cultural and legal obstacles they face – suggests the ceiling for U.S. women in engineering should be as high as we want it to be.

Author Profile: @ericiversen