This spring issue of the Journal of Expanded Learning Opportunities (JELO) launched at the 2016 BOOST conference and features a conversation about quality programming in afterschool, an article on the role that social emotional learning can play to close the achievement and learning gaps, and an article focusing on the links between professional development and quality STEM learning experiences.

The JELO serves as an important resource for the expanded learning field as well as makes the connection between research and practice for afterschool program providers and increases public awareness of the expansive work taking place in afterschool programs. This blog features one of the articles in the current issue titled, “Filling in the Gaps: How Developmental Theory Supports Social Emotional Learning in Afterschool Programs” authored by Andrea Canzano, Kenneth A. Anthony II, Ed.D., Elise Scott, M.S. All are with the Connecticut AfterSchool Network.

Abstract:

This paper examines studies, census reports, and afterschool data to shed light on how afterschool programs can help close the opportunity, achievement, and learning gap found in traditional education. The theories of Bronfenbrenner and Gardner can inform programming during out-of-school time, improving the ability of programs to craft curriculum that can close the education gap through social emotional development. Census and afterschool data show that minority and/or impoverished children are most in need of social emotional and academic support, but are given the least access to high quality afterschool programs. Research shows that, while brain-building often stops with early childhood interventions, it is essential for school-age children as well. The paper closes with recommendations for SAFE (sequenced, active, focused, explicit) programming and best practices for implementation.

Keywords: social emotional learning, afterschool, promising practices, program implementation

Filling in the Gaps:

How Developmental Theory Supports Social Emotional Learning in Afterschool Programs

Many of the institutionalized inequalities of the education system hinder the ability to reach learners of every race, socioeconomic standing, and family background equally. Formal public education systems are primarily locally funded, abide by strict curriculum guidelines and standardized assessments, and attempt to decrease the opportunity, achievement, and learning gaps for minorities (U.S. Department of Education, 2014). Afterschool programs have a similar structure, however are unrestricted by curriculum guidelines, standardized accountability, and, for the most part, state and federal mandates. They have the ability to support academic success and social emotional competence through individualization to students’ needs and background.

School curricula are developed with the hope of achieving student success, yet become impeded by challenges within the traditional classroom and the bureaucracy of education. In Smith and Kovac’s (2011) survey, teachers saw preparing students for standardized tests as “reducing the quality of instruction they are able to provide students” (p. 210). Quality instruction cultivates success by connecting students’ social emotional and academic skills. Afterschool programs can facilitate real-life application of academic content through collaboration with teachers and families (Afterschool Alliance, 2011). This article explores ways Afterschool programs can promote and encourage social emotional learning for students who are failing academically or behaviorally within the public education system.

Environmental Contexts

Children’s social emotional development is affected by economic conditions, beliefs, and educational family structures. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2015), 68.2% of single mothers, 81.2% of single fathers, and 59.1% two-parent households are in the workforce. Low-income children are limited by their comparative lack of access to resources and experiences (Bandura, 2001). In addition, high stress levels can affect brain development in regions associated with language and reading (Noble et al., 2015). The United States Department of Education Office of Civil Rights found that “the United States has a great distance to go to meet our goal of providing opportunities for every student to succeed” (U.S. Department of Education, 2014, para. 4). Because of their ability to understand the environments in which their students develop, afterschool programs can help support success for all students.

Bronfenbrenner’s Biological Model of Human Development examines the environmental contexts in which children live (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). Bronfenbrenner focuses on the events a child experiences, or Proximal Processes. The characteristics of the developing Person, the Context of the environment, and the historical Time are all factors in the Proximal Process. Within these processes are systems of influence. The smallest systems have direct contact with the child and the largest systems consist of societal norms that indirectly shape the environment. Afterschool programs are found in the two smallest systems that hold direct influence over the child, the microsystem and mesosystem (Bronfenbrenner, 1994).

Each microsystem consists of people and places that are frequent in the developing child’s life (e.g., home, grandma’s house, school, afterschool, etc.). Through their microsystems, the child develops tools they will use “to accomplish the tasks and goals that give meaning, direction, and satisfaction to their lives” (Bandura, 2001, p. 4).

Influencers in each microsystem provide basic necessities and maintain consistent structure. In environments which do not provide these prerequisites, social emotional development is focused on avoiding dysfunction rather than advancing competence. Students are likely to develop traits that best fulfill the behavioral expectations to which they are exposed (Thompson, 2014). For students from an unstable home microsystem, social expectations in structured environments such as school or afterschool may cause challenging behavior. These environments have expectations that are often unfamiliar or uncomfortable.

For this reason, learning about the social norms and behavioral expectations in each child’s home environment microsystem is our first recommendation. This is one step that can help reduce the achievement gap.

Afterschool Context

If an afterschool program’s behavioral expectation varies drastically from those in other environments, afterschool program educators must understand how to work within both systems to further students’ social emotional competence. Durlak and Weissberg (2007) proved that when afterschool programs implemented sequenced, active, focused, and explicit (SAFE) curriculum, it enhanced students’ social emotional development. This helped close the gap in supports, resources, and interactions that low-income children experience.

For example, Paul and Sally have similar socioeconomic status, family structure, and live in a similar neighborhood but have different experiences growing up (see Table 1). At age 3 Sally experiences a major social change at home, and has challenging behaviors due to the bilateral nature of social and emotional development (Lerner, Bowers, Geldhof, Gestsdóttir, & DeSouza, 2012). From ages 5-15, Sally adapts as she receives guidance around these behaviors, and develops greater social emotional competence, with stronger relationships and improved communication. As Paul develops, he only learns the limited communication skills he’s accustomed to at home, causing him complications in other environments where communication is open. During the final and greatest variance between their environments, Sally’s family becomes financially unstable, limiting their necessities such as the food budget. Sally’s academic success and communication skills began to suffer. Her home and afterschool program microsystems may be able to hypothesize that hunger or stress is the cause of the undesirable behaviors and academic trouble, and collaborate to find a solution.

Bronfenbrenner and Morris (2006) assert that when dealing with a destabilized home environment there is “greater impact in reducing dysfunction rather than in enhancing [a child’s] knowledge about and skill in dealing with the external environment” (p. 803). Understanding this position can help afterschool professionals move towards constructive behavior management techniques instead of disciplining behaviors. Over time, the child and their environment (the proximal processes) change, and behavior management and social emotional development goals at home and in the afterschool program need to adapt together to support the child.

These philosophies can apply to students who are in severely disadvantaged situations, where preventing dysfunction is the goal. Disadvantaged situations may include challenges in one or all of the following elements: family structure, socioeconomic standing, neighborhood, parent or guardian education level, instability, and lack of necessities. In these situations, afterschool programs can “improve the quality of the environment” by being a part of the solution, and in turn “increase the developmental power of promising processes” (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006, p. 808). If the family context is unable to intervene, the child’s other microsystems (such as an afterschool program) have the responsibility of intervening.

Children often look to peers for guidance. Within the afterschool program, a student’s peer group is a central component of the microsystem. Peer groups encourage developmentally generative or developmentally disruptive characteristics dependent on their dispositions. Peers can set in motion proximal processes that strengthen or hinder outcomes. In afterschool programs, advancing students’ social emotional development through building developmentally generative characteristics within peer groups is essential.

The contexts of family, school, afterschool, and peer groups have the opportunity to work together towards encouraging positive outcomes, understanding each student’s needs, and making resources accessible. A student’s brain-building, through the use of enriching experiences, is extremely prevalent in early childhood interventions (Shonkoff, Boyce, & McEwen, 2009; Lenroot & Giedd, 2006).

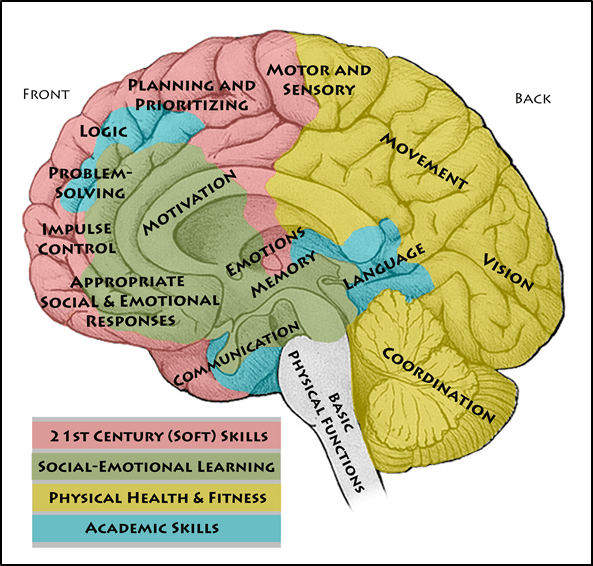

By age 5, the brain has reached 90% of its adult size, but is continuously undergoing transformation. Between ages 4 to 18, the part of the brain controlling emotions, memory, and language changes dramatically. The area that regulates communication across parts of the brain and links brain function to behaviors and feelings continues to change and mature at a rapid rate beyond the age of 40. This means that brain-building must continue through school-age and beyond (Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006; Lenroot & Giedd, 2006; Nagy, Westerberg, & Klingberg, 2004; Paus et al., 2001). Figure 1 illustrates numerous ways that afterschool programs stimulate continued brain development in school-age youth. Afterschool programs have the potential to facilitate development in nearly every area of the brain through their unique blending of academic, social-emotional, physical, and 21st century learning experiences (Shernoff, 2010; Beets, Beighle, Erwin, & Huberty, 2009; Silva, 2008; Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006; Zeif, Louver, & Maynard, 2006; Posner & Vandell, 1999) ( see Figure 1).

Figure 1. How Afterschool Impacts Brain Development. Reprinted from Brain-Building in Afterschool by E. Scott, 2016, Hartford, CT: Connecticut After School Network. Retrieved from https://ctafterschoolnetwork.org/brain-building-in-afterschool/. Copyright 2016 by the Connecticut After School Network. Reprinted with permission.

Afterschool programs which have an understanding of the unique contexts that influence each child work to close gaps in the ability of the home and other microsystems to advance development. Programs can identify what is missing for a child to have the social emotional skills to be successful in all contexts. Equipped with an awareness of the gaps, programs can help children develop skills in areas that are lacking.

Reaching all Learners through SAFE Curriculum

Reaching all learners is an overwhelming task. Yet the need is high. According to Baker (2014), the average Caucasian student at age 13 reads at the same level as an African-American student at 17. In addition, 61% of African-Americans and 50% of Latinos living in low-income situations would enroll their students in structured and focused afterschool programs if they were available (Afterschool Alliance, 2009). Each student has a unique social emotional skill set and individual learning style. The Campaign for Educational Equity emphasized that increasing access to high-quality afterschool programs is essential to achieving educational equity (Afterschool Alliance, 2013).

Vandell, Reisner, and Pierce (2007) demonstrated the potential of afterschool programs to increase academic scores through application of personal skills and talents. Programs can partner with traditional education to build complimentary learning. Afterschool activities can encourage 21st Century Skills such as problem solving, teamwork, and critical thinking (Hart, 2008). Though these skills may be addressed in the traditional classroom, a meta-analysis conducted by Durlak, Weissberg, and Pachan (2010) illustrated that when students participate in the skills being taught, such as by the Active element of SAFE curriculum, acquisition of knowledge occurs in a more effective and efficient manner.

The ability to continually reach and encourage academic growth in afterschool programs requires an understanding of progression in academic knowledge, environmental influences, and learning styles. Understanding these characteristics enables afterschool programs to create engaging activities while promoting academic growth. It is essential that learning builds on the background knowledge students receive from the school curriculum, social emotional capabilities, and school philosophies. Once there is an understanding of a student’s social emotional development, thoughtfully structured curriculum is a key to their success. Afterschool programs which integrate Sequenced, Active, Focused, and Explicit (SAFE) curriculum have shown positive social emotional development gains (Durlak, Weissberg, & Pachan, 2010). This includes structuring behavioral expectations similar to the school district students attend, collaboration with teachers to expand on curriculum, and developing partnerships that facilitate joint training between school and afterschool program personnel in current teaching techniques. For this reason thoughtful implementation of SAFE curriculum is a tool to be utilized when introducing social emotional curriculum within afterschool programs.

Considering Student Ability and Interest in SAFE Curriculum

Student interest and talents should drive the afterschool program curriculum, and be based on SAFE components. When incorporating explicit activities, students must comprehend the skills they are practicing in order to make improvement (Durlak, Weissberg, & Pachan, 2010). In afterschool, it is important for staff to avoid the mistake of providing students with simplistic activities.

Gardner’s Seven Multiple Intelligences provide afterschool programs the tools to implement SAFE activities. Current criticisms of Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences include lack of empirical support and flaws in some of the research supporting the theory (McConnell, 2015). However Armstrong (2009) asserted that the Multiple Intelligence model is conducive to the needs of after school professionals when developing complex instruction which encourages confidence and trust in oneself and others.

The process of participating in activities not only teaches students how to complete the task (e.g, build with Legos) but also teaches social strategies (e.g., building with Legos with a partner). Gardner and Hatch (1989) assert that individuals have multiple ways of showing intelligence. The intelligences are Logical-Mathematical, Linguistic, Spatial, Musical, Bodily-Kinesthetic, Interpersonal, and Intrapersonal. Afterschool program staff can gather information on students’ learning styles from teachers, guardians, and their own observations.

These intelligences are listed individually, however Gardner found that they rarely act independently (Brualdi, 1996; Gardner & Hatch, 1989). This is something for afterschool programs to consider. Due to the large number of students a program can serve daily, it would be nearly impossible to consider each student’s environmental history, social emotional zone of development, and individual interests when creating activities. However, Gardner states that to have a functional society all seven intelligences must be present. For education, this means that focusing solely on Language Arts and Math skills is actually a hindrance to intelligences outside of logic and verbal (Gardner & Hatch, 1989; Brualdi, 1996). Afterschool programs can encourage student interest and talents by focusing on activities that reinforce traditional education skills and foster success through many or all intelligences. Reflecting on a student’s abilities (intelligences) and their contribution to an activity can prevent a student with low self-efficacy from having a negative experience and reacting with challenging behaviors. Figures 2 and 3 feature example activities which illustrate this.

Figure 2. Activity with Skill-Level Adjustments, Broken Square Example

Figure 3. Activity with Skill-Level Adjustments, Copy Cat Example

Case Studies

The New Hampshire Extended Learning Opportunities (ELO) targets at risk students and promotes success through student interest. One teacher learned that potential high school dropouts enjoyed rap, but struggled with traditional English classes. The teacher worked collaboratively with students to develop curriculum which challenges them to display confidence in their own abilities, and reflect on the experience. Through following interest, the curriculum incorporated musical intelligence and specific developmental needs allowing the students to experience academic success and the highest level of cognition. These students were able to develop individualized learning portfolios, reaching a knowledge level of metacognition and cognitive level of creation (Heer, 2012) versus failing English.

This model demonstrates what partnerships between school and community providers can accomplish. By understanding student needs in adverse developmental situations this teacher was able to show success while applying the highest level of thinking skills. In the hierarchy of cognitive processes, many high order skills require social emotional abilities, such as working in inter- and intrapersonal settings, reflection, direct purpose, confidence, and the ability to respond constructively to environmental influences. Using multiple intelligences and social emotional abilities can encourage positive experiences for students. Incorporating daily strategies that build on students’ interests and needs is a good starting point for afterschool programs to implement social emotional curriculum (as shown in Appendix A).

An excellent example of this is the California Afterschool Outcome Measures Project (CAOMP), which tracks data based on student input, school staff academic and behavioral data, as well as afterschool professionals’ interaction quality and availability of level appropriate activities. CAOMP’s focus within social emotional growth surveys afterschool professionals’ and classroom teachers’ observations of student social behavior, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, and work habits. CAOMP incorporates student surveys initiating self-reflection of students’ social emotional development regarding interactions with afterschool professionals, interactions with peers, and interest and engagement in activities. Due to programs participating in persistent data collection such as CAOMP, there is evidence that social emotional curriculum supports closing achievement gaps (Vandell, 2013).

A recent case study by Humans of New York story cited a teacher at the Mott Hall Bridges Academy who used to run an afterschool program for 5-12 year olds. One activity he created was a group building challenge (using manila folders, tape, and straws). The first attempt at implementation was unsuccessful. The next day, however, he bought yellow hard hats, and found “they transformed the kids. The hats made them feel like builders. . . . Other kids saw them through the window and asked to join, until all the hats were gone” (Stanton, 2015, para. 1). This one simple act encouraged social emotional gains, high levels of cognitive functioning, and academic skills.

Ramapo for Children is an organization which offers programs for youth who have academic, social, or emotional special needs. Their mission, to “help young people learn to align their behaviors with their aspirations,” mirrors the intention of the building challenge (Ramapo for Children, About Us, n.d., para. 2). The children’s social emotional toolbox develops through a four-tiered pyramid: (a) relationships and role models, (b) implementation of clear expectations, (c) structures and routines, adapting to individual needs, and (c) responding, reflecting, and repairing. Similar to SAFE programs, this pyramid is sequenced, responds actively to the needs of individuals, focuses on data driven practices and provides explicit structure for participants. The success of their toolbox is exemplified through their partnerships with Urban Assembly, which is “dedicated to empowering underserved youth by providing them with the academic and life skills necessary for postsecondary success” (The Urban Assembly, Our Mission, n.d., para. 1).

The parallel missions allowed Ramapo and Urban Assembly to provide teachers and students with trainings to develop social and emotional needs demonstrated through their partnership with the New Technology School located in a Harlem, NY public housing project. Jeff Chetriko, principal of New Tech in Harlem, stated the trainings, “gave students an opportunity to see a world outside of Harlem and helped prove to them that they are worth something,” creating a school atmosphere that students and staff were proud of due to the new ability to talk about issues versus the previous norm of resorting to violence (Ramapo for Children, Our Impact, n.d., para. 6). The school previously was unsafe, unwelcoming, and ultimately counterproductive in providing students with quality education; however, there was a 33% reduction in suspensions and 40% reduction in behavioral incidents after the installation of a social emotional curriculum (Ramapo for Children, Our Impact, n.d., para. 3).

Conclusion: Filling in the Gaps with SAFE Afterschool

Youth in adverse environments are more likely to be unsupervised in the hours after school then youth in more advantageous environments (Afterschool Alliance, 2014). Likewise, parents reported that programs in their area often did not include challenging and enriching environments (Afterschool Alliance, 2014). This seems to suggest that students most in need of social emotional development are the least likely to receive the necessary support. Understanding students’ social emotional processes, personal interest, and abilities in these communities can help develop SAFE afterschool programs and begin to close the opportunity, learning, and achievement gaps. There is need for SAFE and purposefully designed activities in afterschool programs where the factors of low socioeconomic standing, unstable environments, and low educational funding are pervasive. The ability to function productively, understand and thrive in institutionalized social systems, and achieve social emotional competence is required to succeed in today’s societal structure (Bandura, 2001).

SAFE afterschool programs have been found to improve students’ self-efficacy and academic performance, while decreasing developmentally disruptive characteristics. Durlak and Weissberg (2007) conducted a meta-analysis of 69 different programs which served children ages 5-18 across the country. Programs which continuously used SAFE structure and simultaneously aligned with the school day improved students standardized test scores, improved social behaviors, and reduced problem behaviors compared to programs without consistent social emotional curriculum (Bennett, 2015; Durlak & Weissberg, 2013; Vandell, Reisner, & Pierce, 2007) (see Figure 4). Afterschool programs which connect social emotionally centered curriculum and student interest can utilize the toolboxes provided through the example of Ramapo for Children and the California Afterschool Outcome Measures Project.

Success develops from a student’s ability to use cognitive and social emotional skills collectively (Farnham, Fernando, Perigo, Brosman, & Tough, 2015). Developing these competencies is the first step to help students succeed in traditional education. Afterschool programs are in a position to make change and impact the closing of the opportunity, learning, and achievement gaps in education.

Figure 4. Average percentile gains on selected outcomes for participants in SAFE vs. other afterschool programs. Reprinted from Expanding Minds and Opportunities: Leveraging the Power of Afterschool and Summer (p. 196), by T. K. Peterson (Ed.), 2013, Washington, DC: Collaborative Communications Group. Copyright 2013 by Collaborative Communications Group. Reprinted with permission.

Recommendations for Practitioners

Afterschool programs and educators, particularly those who serve children from low-income or at-risk families, are encouraged to consider the following steps. First, consider the contexts or microsystems that each child in your program has been exposed to. Are any unmet needs impacting the child’s behavior or performance? What skills has the child developed as a result? What skills are missing or need to be developed more fully?

Second, keeping this insight in mind, consider how your afterschool program can be a support. Can you help families find or access resources to address unmet needs? How can your behavior management strategies encourage a positive behavior that builds a social emotional skill (like communication or self-regulation) rather than just halting an unwanted behavior? How can you build up self-esteem in areas where it may be lacking?

Third, build and implement a SAFE curriculum. Sequence your activities, so that each activity builds on the ideas and skills explored in the activities that came before. Start by thinking in week-long units, with new ideas appearing at the start of the week, and building knowledge and skills as the week progresses. Make your activities Active, so that students participate in fun, hands-on learning, practice new skills, and in activities which are related to their interests. Focus your activities, devoting specific, regularly scheduled time to developing the social emotional and academic skills your students need most. Be Explicit, defining what skills the students are learning and practicing. Tell students before the activity what they will be learning, and afterwards, check in to see if they learned what you were hoping and how they felt about the experience. For more specific ideas and a glossary of terms, explore Appendix A and Appendix B to jumpstart the process of integrating SAFE curriculum to promote social-emotional and academic success in the children you serve.

In 2017, The JELO will publish two issues: a special issue in Spring and a regular issue in the Fall. At this time, they welcome the submission of papers for both the Spring 2017 special and Fall 2017 regular issue. Please visit the blog post from yesterday to learn about the call for papers for more details. The deadline to submit is August 29, 2016. You can also visit Central Valley Afterschool Foundation for more information.

References

Afterschool Alliance. (2009). Afterschool and workforce development: Helping kids compete. Issue Brief. Retrieved from https://www.afterschoolalliance.org/issue_36_Workforce.cfm

Afterschool Alliance. (2011). New progress reports find every state has room for improvement in making afterschool programs available to all kids who need them. Retrieved from https://www.afterschoolalliance.org/press_archives/ National-Progress-Report-NR-10202011.pdf

Afterschool Alliance. (2013). The importance of afterschool and summer learning programs in African-American and Latino communities (2013). Issue Brief. Retrieved from https://www.afterschoolalliance.org/printPage.cfm?idPage=BF375223-215A-A6B3-02D01AED270CEDCA

Afterschool Alliance. (2014). America after 3PM: Afterschool programs in demand. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://afterschoolalliance.org/documents/AA3PM-2014/AA3PM_National_Report.pdf

Armstrong, T. (2009). Multiple intelligences in the classroom (3 ed.). ASCD: Alexandria, VA.

Baker, P. (2014). Bush urges effort to close black and white students’ achievement Gap. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/11/us/politics/bush-urges-effort-to-close-black-and-white-students-achievement-gap.html

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Reviews: Psychology, 1-18.

Beets, M. W., Beighle, A., Erwin, H. E., & Huberty, J. L. (2009). After-school program impact on physical activity and fitness: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(6), 527-537.

Bennett, T. L. (2015). Examining levels of alignment between school and afterschool and associations on student academic achievement. Journal of Expanded Learning Opportunities (JELO), 1(2), 4-22.

Blakemore, S. J., & Choudhury, S. (2006). Development of the adolescent brain: Implications for executive function and social cognition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(3‐4), 296-312.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994) Ecological models of human development. In T. Husen, & T. N. Postlephwaite, (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (2nd ed., Vol. 3, 1643-1647). Oxford, England: Pergamon.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R.M. Learner, & W.E. Damon (Eds.). Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 1: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., Vol. 1, 793-825). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Brualdi, A. (1996). Multiple intelligences: Gardner’s theory. ERIC Digest. Eric Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation, Washington D.C. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED410226

Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2007). The impact of after-school programs that promote personal and social skills. Chicago, IL: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning.

Durlak, J., & Weissberg, R. (2013). Afterschool programs that follow evidence-based practices to promote social and emotional development are effective. In T. K. Peterson (Ed.), Expanding minds and opportunities: Leveraging the power of afterschool and summer learning for student success, (pp.194-198).Washington, DC: Collaborative Communications Group.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., & Pachan, M. (2010). A meta-analysis of afterschool programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45, 294–309.

Farnham, L., Fernando, G., Perigo, M., Brosman, C., & Tough, P. (2015). Rethinking how students succeed. Stanford Social Innovation Review Retrieved from https://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/rethinking_how_students_succeed

Gardner, H., & Hatch, T. (1989). Educational implications of the theory of multiple intelligences. Educational Researcher, 18(8), 4-10.

Hart, P. (2008). Key findings on attitudes toward education and learning. Peter Hart and Associates, Inc.: Washington D.C.

Heer, R. (2012). A model of learning objectives based on a taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Iowa State University: Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching

Lenroot, R. K., & Giedd, J. N. (2006). Brain development in children and adolescents: insights from anatomical magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 30(6), 718-729.

Lerner, R. M., Bowers, E. P., Geldhof, G. J., Gestsdóttir, S., & DeSouza, L. (2012), Promoting positive youth development in the face of contextual changes and challenges: The roles of individual strengths and ecological assets. New Directions for Youth Development, (pp.119-126). Hoboken, NJ; John Wiley & Sons.

McConnell, M. (2015) Reflections of the impact of individualized instruction. National Teacher Education Journal. (53-56).

Nagy, Z., Westerberg, H., & Klingberg, T. (2004). Maturation of white matter is associated with the development of cognitive functions during childhood. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 16(7), 1227-1233.

Noble, K. G., Houston, S. M., Brito, N. H., Bartsch, H., Kan, E., Kuperman, J. M., . . . Sowell, E. R. (2015). Family income, parental education and brain structure in children and adolescents. Nature Neuroscience, 18(5), 773-778.

Paus, T., Collins, D. L., Evans, A. C., Leonard, G., Pike, B., & Zijdenbos, A. (2001). Maturation of white matter in the human brain: A review of magnetic resonance studies. Brain Research Bulletin, 54(3), 255-266.

Peterson, T.K. (Ed.). (2013). Expanding minds and opportunities: Leveraging the power of afterschool and summer learning for student success. Washington, DC: Collaborative Communications Group.

Posner, J. K., & Vandell, D. L. (1999). After-school activities and the development of low-income urban children: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 35(3), 868.

Quinton, S. (2014). The race gap in high school honors classes. National Journal Retrieved from https://www.nationaljournal.com/next-america/education/the-race-gap-in-high-school-honors-classes-20141211

Ramapo for Children, About us. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.ramapoforchildren.org/about-ramapo

Ramapo for Children, Our impact. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.ramapoforchildren.org/our-impact

Shernoff, D. J. (2010). Engagement in after-school programs as a predictor of social competence and academic performance. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45(3-4), 325-337.

Shonkoff, J. P., Boyce, W. T., & McEwen, B. S. (2009). Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: Building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. Jama, 301(21), 2252-2259.

Silva, E. (2008). Measuring skills for the 21st century. Education Sector, p. 2. Retrieved from https://dc2.bernan.com/KCDLDocs/KCDL29/CI%20K~%20389.pdf.

Smith, J. M., & Kovacs, P. E. (2011). The impact of standards-based reform on teachers: The case of No Child Left Behind. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 17(2), 201-225. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2011.539802

Stanton, B. (2015). Humans of New York. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/humansofnewyork/photos/pb.102099916530784.-2207520000.1456270237./877920092282092/?type=3&theater

Thompson, R. (2014). Stress and child development. The Future of Children (1st ed., Vol. 24, pp. 41-55). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University.

The Urban Assembly, Our mission. (n.d.). Mission. Retrieved from https://urbanassembly.org/mission

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor. (2015). Employment characteristics of families – 2014. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/famee.pdf

U.S. Department of Education. (2014). Expansive survey of America’s public schools reveals troubling racial disparities. Retrieved from https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/expansive-survey-americas-public-schools-reveals-troubling-racial-disparities

Vandell, D. (2013). Afterschool program quality and student outcomes: Reflections on positive key findings on learning and development from recent research. In T. K. Peterson (Ed.), Expanding minds and opportunities: Leveraging the power of afterschool and summer learning for student success. (pp. 180-186). Washington, DC: Collaborative Communications Group.

Vandell, D., Reisner, E., & Pierce, K. (2007). Outcomes linked to high-quality afterschool programs: Longitudinal findings from the study of promising afterschool programs. Washington, DC: Policy Studies Associates. Retrieved from https://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED499113.pdf.

Zief, S. G., Lauver, S., & Maynard, R. A. (2006). Impacts of after-school programs on student outcomes: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 2(3).

Appendix A

Jumpstart Social Emotional Learning: Activities to Understand Your Students’ Interests and Experiences and to Build Personalized Social Emotional Learning

Thumb Up, Thumb Flat, Thumb Down

- When students arrive and throughout the program, have them show “Thumb Up” if they are having a good day, “Thumb Flat” if they are having an okay day, or “Thumb Down” if they are having a difficult day. Incorporate this into the staff’s routine with the students, having staff show how their day is going with their thumbs as well. It is a simple tool to check in with the students and for students to check in with staff, leading to a safe, understanding atmosphere.

One Word Share

- Upon arrival, have students and staff members individually choose one word that describes them right now. Go around in the large group or in small groups sharing the word. No discussion of the word anyone chose is allowed, which creates the safety to be honest. They can share an emotion they are having, an interest of theirs, or even something silly; the intent is to promote authenticity and build knowledge of each person over time, not simply in the moment of sharing.

Silent Cheers

- Have each staff member and student go around and say something they enjoy (e.g., tacos, soccer, painting, math). If it is something that you like as well, silently wave your hands in the air as if you were cheering. This will help staff and students cultivate relationships based on common interests and learn what students are interested in, to support interest-based activity development.

Commonality Line

- In an area that students and staff can stand and step forward, create two lines facing each other. Have one person say a statement that applies to them. (e.g., “I have two sisters,” “I am 10 years old,” escalating to personal statements, “I am in foster care,” “I have two moms,” etc.) Everyone that the statement applies to silently steps forward for a brief moment, looking around, and then returns to the original line. As the activity progresses, the hope is to learn more about the students and staff’s home-life and encourage understanding that we have similar and different experiences but we are all still standing together.

Safe Box

- Create a box in which students and staff can put writings or drawings anonymously. On a predetermined time randomly choose a writing or drawing from the box to share. The box should be safe and have no instructions other than you are not allowed to bring others down. You may vent about anything but cannot specifically mention names or reference specific people (e.g., “I am frustrated with the way Johnny bothers me during homework club” is not allowed, but “I am frustrated when people distract me during homework club” is fine). This activity is designed to build discussion and empathy, and should be implemented once a safe atmosphere has been created among the staff and students.

Appendix B

Glossary of key terms

Achievement Gap: refers to any significant and persistent disparity in academic performance or educational attainment between different groups of students, such as white students and minorities, for example, or students from higher-income and lower-income households.

Assistance Assumption: skills that students are able to accomplish with assistance from a more competent peer or adult (their instructional level).

Bloom’s Taxonomy: a classification system used to define and distinguish different levels of human cognition (i.e., thinking, learning, and understanding).

Bodily-Kinesthetic Intelligence: the ability to use one’s mental abilities to coordinate one’s own bodily movements. This intelligence challenges the popular belief that mental and physical activity are unrelated.

Chronosystem: encompasses change or consistency over time not only in the characteristics of the person but also of the environment in which that person lives (e.g., changes over the life course in family structure, socioeconomic status, employment, place of residence, or the degree of chaos and ability in everyday life).

Cognitive Process Dimension: represents a continuum of increasing cognitive complexity — from lower order thinking skills to higher order thinking skills.

Complex Instruction: Cooperative learning is a form of classroom instruction that structures collaborative interactions among learners to achieve the teacher’s learning goals. This includes assigning competencies, multiple abilities, heterogeneous grouping, and equalization of academic status.

Context: a series of nested systems that affect the developing person ranging from micro to macro.

Developmental Competence: demonstrated acquisition and further development of knowledge and skills — whether intellectual, physical, social emotional, or a combination of them.

Developmentally Disruptive: includes such characteristics as impulsiveness, explosiveness, distractibility, inability to defer gratification, or, in a more extreme form, ready resort to aggression and violence; in short, difficulties in maintaining control over emotions and behavior. At the opposite pole are such Person attributes as apathy, inattentiveness, unresponsiveness, lack of interest in the surroundings, feelings of insecurity, shyness, or a general tendency to avoid or withdraw from activity.

Developmental Dysfunction: refers to the recurrent manifestation of difficulties on the part of the developing person in maintaining control and integration of behavior across situations.

Developmentally Generative: involves such active orientations as curiosity, tendency to initiate and engage in activity alone or with others, responsiveness to initiatives by others, and readiness to defer immediate gratification to pursue long-term goals.

Exosystem: comprises the linkages and processes taking place between two or more settings, at least one of which does not contain the developing person, but in which events occur that indirectly influence processes within the immediate setting in which the developing person lives (e.g., for a child, the relation between home and the parent’s workplace; for a parent, the relation between the school and the neighborhood group).

Generality Assumption: skills that students are able to accomplish without assistance (their independence level).

Intelligence (Gardner): the capacity to solve problems or to fashion products that are valued in one or more cultural setting.

Knowledge Dimension: classifies four types of knowledge that learners may be expected to acquire or contract —ranging from concrete to abstract.

Learning Gap: the difference between what a student has learned (i.e., the academic progress he or she has made) and what the student was expected to learn at a certain point in his or her education, such as a particular age or grade level. A learning gap can be relatively minor—the failure to acquire a specific skill or meet a particular learning standard, for example—or it can be significant and educationally consequential, as in the case of students who have missed large amounts of schooling.

Linguistic Intelligence: involves having a mastery of language. This intelligence includes the ability to effectively manipulate language to express oneself rhetorically or poetically. It also allows one to use language as a means to remember information.

Logical-Mathematical Intelligence: consists of the ability to detect patterns, reason deductively and think logically. This intelligence is most often associated with scientific and mathematical thinking.

Macrosystem: consists of the overarching pattern of micro-, meso-, and ecosystems characteristic of a given culture or subculture, with particular reference to the belief systems, bodies of knowledge, material resources, customs, life-styles, opportunity structures, hazards, and life course options that are embedded in each of these broader systems.

Mesosystem: comprises the linkages and processes taking place between two or more settings containing the developing person (e.g., the relations between home and school, school and workplace, etc.).

Microsystem: a pattern of activities, social roles, and interpersonal relations experienced by the developing person in a given face-to-face setting with particular physical, social, and symbolic features that invite, permit, or inhibit engagement in sustained, progressively more complex interaction with, and activity in, the immediate environment. Examples include such settings as family, school, peer group, and workplace.

Musical Intelligence: encompasses the capability to recognize and compose musical pitches, tones, and rhythms. (Auditory functions are required for a person to develop this intelligence in relation to pitch and tone, but not needed for the knowledge of rhythm.).

Opportunity Gap: refers to the ways in which race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, English proficiency, community wealth, familial situations, or other factors contribute to or perpetuate lower educational aspirations, achievement, and attainment for certain groups of students.

Person: describing the developing person distinguished most by three types of characteristics that are most influential in shaping the course of future development through the capacity to affect the direction and power of proximal processes through the life course: dispositions that set proximal processes in motion and sustain their operation, resources of ability, experience, knowledge, and skill, demand characteristics that invite or discourage reactions from social environment that can foster or disrupt the operation of proximal processes.

Personal Intelligences: includes interpersonal feelings and intentions of others–and intrapersonal intelligence–the ability to understand one’s own feelings and motivations. These two intelligences are separate from each other. Nevertheless, because of their close association in most cultures, they are often linked together.

Potential Assumption: skills that are within a student’s potential (their challenge level).

Proximal Process: particular forms of interaction between organism and environment that operate over time and are posited as the primary mechanisms producing human development.

Spatial Intelligence: gives one the ability to manipulate and create mental images in order to solve problems. This intelligence is not limited to visual domains–Gardner notes that spatial intelligence is also formed in blind children.

Time: broken into three successive levels: microtime refers to continuity versus discontinuity in ongoing episodes of proximal processes, mesotime is the periodicity of these episodes across broader time intervals, such as days and weeks, macrotime focuses on the changing expectations and events in larger society, both within and across generations, as they affect and are affected by processes and outcomes of human development over the life course.

Zone of Proximal Development: the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers.

Author Profile: @boost-collaborative